|

||

|

MORE WORDS...

|

“THE

MYTHS OF ALKAN”

|

|

The

American pianist Oscar Levant once said of George Gershwin that there were so many myths

and exaggerated stories about him “even the lies about him are being distorted”!

The same could be said of Alkan, the French Jewish composer who lived next door to Chopin

in |

|

|

After his death his music continued to be admired and studied by both Debussy and Ravel, and championed by such pianists as Busoni and Rachmaninov. But it wasn’t until the first LPs of his music began to appear in the 1960s (in particular the recordings of Alkan advocates Raymond Lewenthal and Ronald Smith) that the public got a chance to really get to know the music of this most unusual and distinctive musical figure. When a composer has been neglected for many years, as has been the case of Charles-Valentin Alkan, it's not always easy to reawaken public interest. It's not enough, unfortunately, to let the music simply speak for itself. Something more dramatic is required, particularly in our sound-bite driven media age. Thus in the 1960s, when Alkan's revival began, facts about Alkan’s life and his music often became exaggerated to attract attention and new myths grew up on top of old ones. |

||

|

||

In dispelling some myths about Alkan one feels almost like a spoil sport, as in the dramatic story of his unusual death, crushed by a falling book case as he reached for a copy of the Talmud from the top shelf. This story has become part of the folklore surrounding Alkan. Sad to say, the story is not true. The truth is more interesting … and more tragic. In fact Alkan's death in 1888 seems to exemplify the tragedy of his life: living alone, it appears that he collapsed and was trapped by a piece of falling furniture for more than 24 hours before being discovered by callers who were able to drag him free. He died in his apartment a few hours after being rescued. The apocryphal story about his being crushed by a falling book case has helped to maintain the myth of a highly eccentric composer. |

|

|

Describing

someone as 'eccentric' tends to have the side effect of dehumanising them; thus Alkan began to be seen as a

strange and even cold individual, whose impossibly difficult piano music was

supposed to exhibit the same characteristics, and whose final demise was rather

comical. In truth, Alkan was an intelligent, lively, humorous and warm person (all

characteristics which feature strongly in his music) whose only crime seems to have been

having a vivid imagination, and whose occasional eccentricities (mild when compared with

the behaviour of other 'highly-strung' artistes!) stemmed mainly from his hypersensitive

nature. As for Alkan’s 'impossibly difficult' piano scores, frequently described as setting tremendous, sometimes insurmountable technical challenges for the performer: alas this is also part of the Alkan legend that has been so exaggerated that is has possibly now become one of the biggest obstacles to getting his music more widely known. Initially it was a great way to attract publicity when Alkan advocates such as Raymond Lewenthal and Ronald Smith played up the difficulties of the music. It seemed an obvious way of drawing attention to music that is after all often extremely virtuosic in character. It was a great way for the music to get noticed and it worked. But in attracting the public it appears to have scared off pianists! And Alkan needs pianists! The more his music is performed, and the more variety of interpretations his music receives the better it will be for the composer. Make no mistake, Alkan’s music, in his more demanding scores isn’t easy to play, but the truth is that most of the music, while sometimes taxing - particularly from a stamina point of view, is still well within the limits of any virtuoso pianist, and certainly never as demanding to play as the frequently performed studies of Chopin, or concertos of Rachmaninov. It’s not even true, as is sometimes said, that you need large hands to play Alkan: with one or two exceptions the vast majority of Alkan’s chords fall within the span of an octave. And there is also plenty of scope for the amateur pianist. Many of Alkan’s delightful miniatures fall well within the grasp of amateur pianists and can be extremely rewarding to play (to this end the pianist Ronald Smith prepared for publication a delightful collection of 'easy' Alkan pieces, which was put out by Alkan's publishers, Billaudot of Paris).

As

with most myths, the truth in Alkan's case is often more interesting than the fiction. And

the very stories about Alkan that were exaggerated to attract the public’s attention

are now forming an obstacle to the further exploration of this remarkable mind. It's now

time, for Alkan’s sake to dispel the myths and let people get to know the real human

being behind this remarkable music.

Debussy came across Alkan’s music as a student at the Paris

Conservatoire in the 1870s and was extremely fond of Alkan's miniatures for piano. Like

Chopin, Alkan composed almost exclusively for the piano. Amongst his 75 opus numbers is

the mammoth "Twelve Studies In All The Minor Keys", Opus 39, a work that takes

over 2 hours to perform complete and which contains within it a 3 movement Concerto and a

four movement Symphony, both for solo piano. But in

complete contrast to this work, Alkan also wrote a myriad of delightful miniatures

depicting a wide variety of moods; these are the pieces Debussy was so smitten with.

Listening to these pieces it's easy to hear what attracted Debussy to this music,

particularly in such a piece as "Les Soupirs" from Alkan's set of 48 Esquisses,

with its enticing harmonies, and its musical depiction of a single emotional mood (in this

case ‘sighing’).

Aside

from the difficulties Alkan faced in his career, another much more personal event clearly

left a big emotional scar on the young composer. On

When Alkan wasn’t performing, or grappling with the turmoil of his

private life, his main source of income, as with Chopin, came from teaching. For a while

he was a professor at the Paris Conservatoire. Alkan clearly took his teaching seriously

and was very much looking forward to the possibility of becoming the head of the piano

department at this illustrious institution. He was after all the most distinguished

Parisien pianist eligible for the position when it finally became vacant in 1848. But

internal politics, anti-semitism, and possibly an underlying awareness of Alkan’s

slightly gauche and shy personality led the powers that be to overlook him and appoint

Alkan’s own pupil, Marmontel, to the position: Marmontel was a mediocre teacher of

solfege who could barely play the piano himself, but thanks to this appointment went on to

teach the next generation of French musicians, including Bizet and Debussy, and in 1858

was awarded the Legion of Honour,

Alkan

was a sociable person with a great sense of humour, who always enjoyed a good intellectual

argument with close friends, though he often suffered from acute shyness and

introspection. When his career didn’t blossom as he had hoped, together with the

turmoil of his private life, his introverted side got the better of him and his

introspection invariably turned more often to depression, as he spent more and more time

in his own company. His personality was such that he tended to dwell on the sad events of

his unfulfilled life. Sometimes he could dispel his moods by his work, sometimes not. As

he wrote to his friend Hiller in 1861:

“I’m

becoming daily more and more misanthropic and misogynous…nothing worthwhile, good or

useful to do… no one to devote myself to. My situation makes me horridly sad and

wretched. Even musical production has lost its attraction for me for I can’t see the

point or goal”.

It

was possibly at times like this that Alkan would have emersed himself in his other great

passion outside of music, the study of theology. He had a passionate interest in the

Bible, including the New Testament, his Jewish background notwithstanding. His music is

filled with religious allusions and he once said if he could have his life over again he

would like to set the entire Bible to music! Although his enthusiasm for this daunting

project was never realised he did get as far as a complete translation of the Bible from

Hebrew to French!

As

well as being extremely scholarly and erudite on a vast range of topics, Alkan also had a

tremendous sense of humour (something that he was able to share with his neighbour

Chopin). Alkan’s ability to convey this humour so successfully in music is almost

unique. One of Alkan’s most notorious pieces is his "Funeral March on the Death

of a Parrot" (often mistakenly referred to as "Funeral March for a Dead

Parrot", though the reference to Monty Python's famously brilliant sketch is tempting

to make!). Alkan's own parrot memorial is an incredibly witty, clever, and marvellously silly

piece of music, and is actually a parody of Rossini, who had a penchant for parrots. The

work is scored for mixed voices and an unusual combination of wind instruments and

virtually the sole text is the French equivalent of the phrase “Who’s a pretty

Polly?”! Another extremely witty work, though also with great moments of pathos, is

Alkan’s "Le Festin d’Esope" (or "Aesop’s Feast"), a set

of piano variations in which each variation depicts a different animal or scene from

Aesop’s fables. Of course laughter and pathos are two very interlinked human

emotions, and not surprisingly, pathos is a characteristic of Alkan’s music

that’s always close to the surface. In his marvellous piano prelude, "The Song

Of The Mad Woman On The

Away

from the vivid imagery of Alkan’s imagination, outwardly his life was very quiet and

uneventful. But every once in a while the regular routine of teaching and composing (and

translating the Bible) was interrupted by a sudden emergence back onto the concert

platform. In fact, later in his life, when the composer was in his 60th decade,

he began a regular, annual series of recitals in "I couldn't begin to describe what happened to

the great Beethovenian poem — above all, the Arioso and the Fugue, where the melody,

penetrating the mystery of Death itself, climbs up to a blaze of light, affected me with

an excess of enthusiasm such as I have never experienced since. It had greater intimacy and was more humanly moving than

Liszt's performance...".

Another

account of Alkan’s playing, from a pupil of Liszt who heard Alkan play towards the

end of his life, describes how Alkan's performance retained an extraordinarily youthful

quality despite his appearance, which was frail and older than his years. Alkan’s last years were lonely and sad. He never married and his loneliness caused him much sorrow and despair. He died alone at the age of 74, not killed by a falling book case, and having outlived his friend and neighbour Chopin by nearly 40 years.

The

pianist Raymond Lewenthal wrote in the 1960s: These notes © 2002 Jack Gibbons |

||

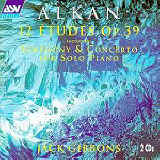

| Copies of Jack Gibbons' highly acclaimed 2 CD recording of Alkan's "Studies In The Minor Keys" Op. 39, plus a selection of Alkan's delightful miniatures, can be ordered from Amazon.com's web site which can be visited by clicking on the image below, which takes you to Amazon.com's music sampler page for this disc. | ||

|

|

Critics Choice, Gramophone Dec.1995 HMV Good CD guide recommendation "Staggering… among the most exhilarating feats of pianism I've heard on disc... Jack Gibbons proves equal to the challenge the music poses not only in terms of virtuosity but, more importantly, artistry… exceptionally impressive" Gramophone |

|