|

||

|

MORE WORDS...

|

|

|

|

George Gershwin was equally at home

in a Broadway theatre and in Carnegie Hall; he seemed to revel in crossing conventional

boundaries. Central to both worlds was his love of the piano. His enthusiasm for regaling |

|

|

For a musician, George Gershwin did not have an auspicious start in life. Born in Brooklyn, New York on September 26, 1898, he grew up on Manhattan’s Lower East Side, where he was known for being a lively and mischievous child more interested in paying and fighting in the street than in anything musical. His parents Morris and Rose Gershovitz (Russian immigrants who had settled in New York in the early 1890s) weren’t particularly musical and it was not until George was 12 years old that the Gershwin household acquired a second-hand upright piano – not for George, but for his older brother Ira to take lessons. In Ira’s own words, “No sooner had the upright been lifted through the window to the front room floor than George sat down and played a popular tune of the day. I remember being particularly impressed by his left hand. I had had no idea he could play and found out – despite his roller-skating activities, the kid parties he attended, the many street games he participated in (with an occasional resultant bloody nose) – he had found time to experiment on a player piano at the home of a friend.” To Ira’s relief the threat of piano lessons vanished! It seems that George had taught himself to play by the unpromising method of fitting his fingers into the keys of the player piano as it played. With his remarkable natural talent George progressed rapidly, and in less than 3 years, at the age of 15, he abandoned school (much to the disapproval of his mother) to become a “piano-pounder” in New York’s Tin Pan Alley for $15 a week. |

||

Gershwin’s first big break came when the

singer Al Jolson agreed to record “Swanee” after hearing one of Gershwin’s

characteristic piano renditions of it at a New York party in 1919. Jolson’s recording

sold over a million copies and almost overnight George Gershwin became a household name.

Meanwhile in the concert field, Gershwin was busying himself with pieces ranging from a

string quarter movement (Lullaby) to a mini-opera (Blue Monday). It’s a common

falsehood often quoted today about Gershwin’s career that in began with success in

the popular song industry before Gershwin’s ambitions as a serious composer asserted

themselves: in reality both careers (of Gershwin the popular song composer and Gershwin

the classical composer) emerged at the same time. In fact his first big hit in New York

was not with a Broadway show, but with a concert work: the first performance of the Rhapsody in Blue in February 1924, was a tremendous

success. From then on Gershwin did not look back in either field, and as his Broadway

career blossomed with such shows as Lady Be Good

(1924), Oh Kay! (1926), Girl Crazy (1930), and Of Thee I Sing (1931), so his status in the concert

hall grew alongside with the Concerto in F

(1925), An American in Paris (1928), Second Rhapsody (1932), Cuban Overture (1932), and the Variations on I Got Rhythm (1934). Gershwin’s

crowning achievement – uniting the worlds of both the theatre and the concert hall

– was his epic opera Porgy and Bess (1935). Right to the end of his all-too-brief

life Gershwin confounded his critics by refusing to be categorized. For him a 32-bar song

was as important as a three-movement concerto (and no less demanding to compose) and he

had no time for musical labels or categorizations: “From any sound critical standpoint, labels mean nothing

at all. Good music is good music, even if you call it ‘oysters’”, he

once wrote.

In 1937

Gershwin was at the height of his powers, as a composer of both serious concert works and

immortal songs; he talking enthusiastically of plans for a string quartet (already

sketched out inside his head), a symphony, and another opera. It seems particularly tragic

that it was precisely at this time that he was suddenly and dramatically cut down; his

sudden death from a brain tumour on July 11th 1937, at the age of only 38,

shocked the world. His friend Edward G. Robinson wrote a moving epitaph: “I value above all things the memory I have of

George Gershwin. George – high-spirited, almost boyish – simple –

unaffected – loveable – and charged with the power to make all things, great and

small, absorbing and significant.”

After

George’s death, his brother Ira, now bereft of a song-writing partner, became a

guardian of his brother’s work. He was George’s greatest advocate and defender

against detractors; normally placid and easy-going, it angered him when he felt his

brother was being unfairly attacked: “Generally,

an unfavourable notice of my brother’s music doesn’t bother me too much. So

someone doesn’t like the ‘Rhapsody’ or ‘American in Paris’ or

whatever it is. So someone is entitled to his opinion. So all right. What does bother me

is when I see phrases like ‘naive orchestration’ or ‘structural

ignorance’ as though my brother were just a terribly talented fellow (which they

grant) who somehow stumbled into the concert hall... With these critics there is an utter

disregard of the facts that George from the age of 13 or 14 never let up in his studies of

so-called classical foundations and that by the time he was 30 or so could be considered a

musicologist (dreadful word) of the first degree besides being a composer. When, in 1928,

he went to see Nadia Boulanger in Paris about studying with her she turned him down on the

grounds that there was nothing she could teach him. And she wasn’t kidding.” Happily

for George Gershwin, the public has always maintained a greater sense of his genius than

any critic. Gershwin, like Chopin before him, trusted and respected the public’s

opinion, and perhaps this is one of the real reasons his music is here to stay. Despite

his all-too-short life, Gershwin made a unique and lasting impression in the world of

music. It is tempting to wonder what else he might have written had he lived longer.

During a radio interview George’s close friend Kay Swift gave the following reply to

this frequently asked question: “We’ll

never know, will we? But it would have been important.” * * * * * * * * *

It was

in the early Tin Pan Alley days that Gershwin developed much of the dazzling and

characteristic piano style that was to become the hallmark of his piano playing. Rapidly

tiring of playing the rather mundane songs he was asked to plug, the teenage Gershwin used

all his ingenuity to devise arrangements and variations to enliven them. Some examples of

these early song improvisations or variations are preserved on the early piano rolls he

cut to supplement his income. Eventually of course he became famous for embellishing his

own songs with elaborate keyboard variations, and some of these too are preserved on piano

rolls and on early electric recordings. Listening carefully to these early recordings one

can hear a serious and imaginative mind at work, the mind of the composer George Gershwin,

experimenting with his songs with a view to their potential development as musical ideas.

The melodies are frequently enhanced by the addition of playful and sometimes complex

counter-melodies above and below the main tune, while the harmonies are bolder than in the

printed sheet music, occasionally showing the influence of Gershwin’s great idol,

Debussy.

Amazingly

(considering their complexity) Gershwin never wrote down his spontaneous piano creations,

although he did publish some show-tune variations in his Song Book of 1932 (nowadays published under the

title Gershwin at the Keyboard); however,

compared with his recordings, the Song Book versions are brief, postcard-type impressions

or vignettes, with much of the complexity of his own playing eliminated. Gershwin’s

own performances, as recorded by him on 78’s in the 1920s, owe much of their rhythmic

drive to his own complex form of stride bass which he habitually used but which he

deliberately chose to exclude from his published Song Book, probably because of its

technical difficulty or perhaps because he felt it would introduce too much of the popular

piano element into what was a slightly more serious context.

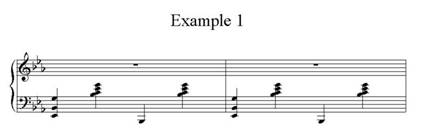

For

those readers who would like to try their hand at improvising in an “authentic

Gershwin” style, it is imperative to master the left-hand stride bass before anything

else. Example 1 illustrates a typical left had stride as used by Gershwin in the key of E

flat. Almost every bar begins with a tenth chord: if this is too much of a stretch for a

small hand it can be rolled upwards, as Gershwin frequently did (play the bottom note

ahead of the beat so that the top note lands on the beat). It is a natural movement since

the hand is in any case about to move in the same direction up to the middle of the

keyboard for the second chord. It is very important that little or no pedal is used when

playing this pattern. As Gershwin himself wrote of this style of music: “The rhythms

of American popular music… should be made to snap, and at times cackle. The more

sharply the music is played the more effective it sounds.” |

||

|

||

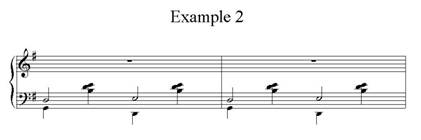

| Once mastered, this left-hand pattern can be adapted to suit any harmony. Gershwin might also vary the left hand with small inner parts (as in Example 2) which are often developed into full-scale counter-melodies, requiring great independence of the fingers. | ||

|

||

|

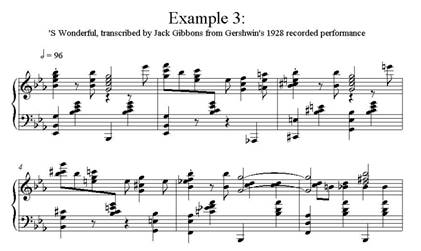

Above this left-hand stride Gershwin

usually played the melody in thick three- and four-note chords spanning an octave, as in

Example 3, which is taken from my transcription of his 1928 recording of “’S

Wonderful”. Notice the delightful syncopation (shared between the hands) in the break

in the melodic phrase in the 2nd and 4th bars. |

||

|

||

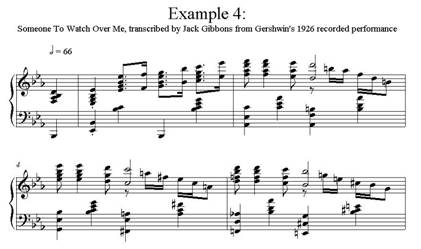

| Example 4, taken from my transcription of Gershwin’s 1926 recording of “Someone To Watch Over Me”, again shows how Gershwin typically fills out melody and harmony in his live keyboard performances. | ||

|

||

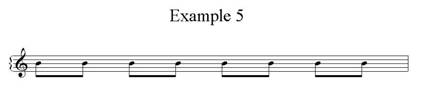

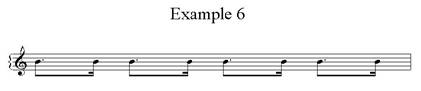

| The written rhythm in the above examples are notated as in the original published songs although the actual rhythms as played by Gershwin in his own recordings are slightly different: the dotted rhythms in Example 4 are played more in the manner of a triplet rhythm, while the ‘straight’ quaver figures in Example 3 are very slightly ‘swung’. However a few words of advice should be given here about ‘swinging the beat’ in Gershwin: contrary to some present-day interpretations, Gershwin’s swinging of the beat (jazzing up the rhythm) was very restrained and very subtle. If anything, in playing a sequence of regular quavers Gershwin’s rhythm is more straight than swung (Example 5): | ||

|

||

| compared with an exaggerated dotted effect that is unfortunately frequently heard in Gershwin performances today (Example 6): | ||

|

||

Gershwin’s exploitation of

all the complexities of rhythm is a study in itself, and too subtle to notate accurately.

It is well worth paying careful attention to his own recordings, particularly the live 78s

(piano-rolls can easily be tampered with and are thus less reliable). Another aspect of

Gershwin’s performance that defies written analysis is the way he conveys

unrestrained enthusiasm by appearing to almost get ahead of himself as he plays. In

reality, by playing a metronome against Gershwin’s recorded performances it’s

possible to see that he isn’t rushing the rhythm at all, but keeping quite a strict

tempo; it’s merely a very skillful illusion created by almost imperceptibly

anticipating the beat, creating a wonderfully eager (but totally controlled) feeling of

almost falling forwards that’s captivating to listen to. To a classical pianist

brought up under the strict regime of holding back the rhythm (sometimes referred to as

‘rhythmic poise’) this style can seem a little unnerving to grasp. As always any

attempt at copying should be monitored carefully: Gershwin’s rhythmic idiosyncracies

(swinging the beat, anticipating the beat, etc.) are extremely subtle and should never be

exaggerated into parodies of the original when imitated. For further guidance see the CD

list of Gershwin’s recordings at the end of this article.

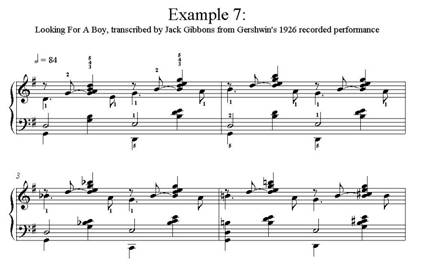

Gershwin

employed any number of often complex and tricky pianistic devices in his improvisations to

enable him to embellish and vary his musical ideas as he wanted. Frequently he expects his

hands to be ‘multi-tasked’, different parts of the same hand playing different

rhythms or melodies simultaneously. One device he was fond of using was the taking of the

theme with his right hand thumb, using the remaining fingers of the right hand to play

extra counter-melodies or accompanying figures. What is particularly remarkable in his

recordings is the subtlety with which he shapes the melody with just the thumb alone.

Example 7 is a typical, taken from my transcription of his 1926 recording of “Looking

For A Boy”: |

||

|

||

The above examples only give the

briefest hint of the inventiveness of Gershwin’s own piano style. Behind all

Gershwin’s spontaneous piano creations is a highly organised and purposeful method;

what might to a casual listener on a first hearing sound like a random selection of

unrelated chords on closer examination turns out to be nothing of the sort: harmonies are

carefully chosen, even down to the doubling or not of crucial harmony notes such as the

third, and behind everything is an intelligent mind, the mind of the genius that was

George Gershwin. And remember, before the appearance of brief extracts in his 1932 Song Book, none of these improvisations were

written down: all these minute details were instead firmly locked inside Gershwin’s

head, and indeed appeared to evolve from performance to performance.

Above

all, to master Gershwin’s original style the aspiring pianist must endeavour to

capture that sense of fun and ingenuousness that was such a hallmark of Gershwin’s

piano playing. As Rouben Mamoulian (director of the original production of Porgy and Bess)

once wrote: “George loved playing the piano for

people and would do so at the slightest provocation… I am sure that most of his

friends, in thinking of George at this best, think of George at the piano. I’ve heard

many pianists and composers play for informal gatherings, but I know of no one who did it

with such genuine delight and verve. George at the piano was George happy.” The best examples of Gershwin’s own piano playing can be heard on the following two recordings:

PEARL Gershwin Plays Gershwin (2 CD set): Includes all

Gershwin’s recordings released commercially in his lifetime. GEMM CDS 9483

MUSICMASTERS

(distributor BMG) Gershwin Performs Gershwin,

a remarkable CD put together by the distinguished Gershwin biographer Edward Jablonski and

featuring the composer’s own rehearsal recordings of his Second Rhapsody and Porgy and Bess (extracts), and recordings of

Gershwin’s radio broadcasts in which his spoken voice can be heard introducing the

music items in his own inimitable style. 5062-2-C.

These notes ©

2002 Jack Gibbons |

||

|

Jack

Gibbons' own transcriptions and reconstructions of Gershwin’s original improvisations

and concert works are available on an award-winning 4-CD series (arranged chronologically)

entitled The Authentic George Gershwin (on ASV: WHL 2074, WHL 2077, WHL 2082, WHL

2110). Click on the image to visit the recordings page to see more details and find links to Amazon.com where the CDs can be purchased. |

|

|